It’s impossible to know exactly when stories of Herakles (Greek)/Hercules (Latin) began to be told. If we are to believe the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, and we probably shouldn’t, Herakles lived more or less around 1300 B.C.E., founding various city states and royal lines in between fighting monsters, killing his children, taking away a tasty food source of divine liver from kindhearted, hungry eagles under the guise of “freeing” minor gods from unjust punishments, cross-dressing, and wrestling Death. This was the sort of thing that made for great stories, and by Herodotus’ time (5th century B.C.E.) the stories were widely told, not just in words, but in pottery, paint, mosaic, sculpture and stone—including the great temples raised in his honor, since by that time, Herakles was regarded as a god.

It’s possible that, as at least some 5th century Greeks believed, Herakles was based on some remote historical figure—possibly a man whose life was so filled with misfortune and bad luck that his contemporaries just assumed a goddess had to be after him—and that, like King Arthur years later, stories about him later grew in the telling, continually reshaped to suit the needs of each teller. It seems more likely, however, that Herakles was never more than a myth—quite possibly a myth with roots stretching back to hunter/gatherer days, later assumed to have a historical existence simply because so many ancient royal families found that convenient. (It always helps to have a hero and a god on the family tree.) His name, after all, suggests this: “Herakles”, or a hero originally connected to the great goddess Hera. Though by the time the tales were recorded, that connection was a relationship of pure hatred and spite.

Hera had reason to be spiteful. If Ovid and other poets are to be believed, Herakles was the son of Hera’s husband Zeus and Alcmene, a lovely mortal woman, who just happened to be Zeus’ great granddaughter. Zeus got around, is what we’re saying, and what ancient poets were happy to verify. (Those heroes and gods in the family tree again.) And this was not something that thrilled Hera, who decided in this case to take her jealous anger out on the little baby, making life hell—sometimes literally—for Herakles, from birth until death.

That hatred may explain part of his appeal. Sure, the guy has super strength. Sure, he gets to sleep with the hottest men and women around the Mediterranean, and sure, his very hot charioteer reportedly can drive more than just chariots, if you get what I’m saying, and pretty much everyone in ancient Greece did. And sure, he gets to travel all over the world, and even to a few locations that might not be entirely within the world (the Garden of the Hesperides, for instance). Sure, he’s on first name terms with gods, who are sometimes even willing to help him out, if at other times content to just watch from the sidelines, if ancient vases are any guide.

But he’s also cursed: he kills his children in a bout of insanity caused by Hera, and ends up poisoned by his own wife. And he’s deeply flawed, with a terrible temper—he kills his music teacher in a sudden fit of rage, and other tales of him suggest that he’s willing to kill first, explain afterwards. His Twelve Labors are not acts of selfless heroism: they are acts of contrition and penance, and the fact that two labors get added to the original ten—two labors that force Herakles to leave mortal worlds for the Gardens of the Hesperides and the underworld of Hades—just emphasizes how hard it is to atone for some mistakes, a truth that at least some of the original audience would have understood.

It helps, too, that all Herakles has is that superstrength. He’s not, for instance, as clever as Odysseus; he doesn’t have a flying horse like Bellerophon; he doesn’t have magical flying shoes and a +5 shield of Petrify Everything like Perseus. He’s somebody that we could all almost be, if, of course, we had divine blood, goddesses attending our births and then pursuing us afterwards, lots of people wanting to sleep with us, including women who are half snake, half human, plus a willingness to get down and dirty in stables if need be.

Ok, maybe not all that much like us.

Whatever the reason, Herakles became more or less the Superman of his day, a popular character whose image appeared everywhere and who was added to several stories whether or not he actually belonged in them. (We are all judging you, Zach Snyder, even in this otherwise unrelated blog post written before I’ve seen anything but the trailer.) He pops up in the story of Jason and the Argonauts, for instance, because of course a boat filled with the greatest of Greek heroes couldn’t take off without Herakles—even if Herakles had to be hastily dumped off the boat mid journey to ensure that he didn’t overshadow Jason. He managed to conquer Troy before the Greeks could. He rescued Prometheus from a tedious life of eternal consumption by eagle, who responded with a long list of heroic things that Herakles would eventually do, like, way to kill the suspense there, Prometheus, thanks. Occasionally he even delivered laughs in Greek comedies.

With so many stories, naturally, discrepancies arose: at one point in Homer, for instance, Herakles is dead, dead, dead, a sad ghost in the underworld, but in multiple other versions, including in Homer, Herakles is alive and well, reconciled (more or less) with Hera, enjoying a life of paradise with her daughter Hebe, goddess of youth, in Olympus. No one could quite agree on the order of the Twelve Labors, except that the last one involved the capture of Kereberos—Hell made for a great ending. Or on just how many people Herakles slept with (although “a lot” seems to be more or less accurate) or how many children he had, or what countries and cities he had visited, although since he eventually became immortal, I, at least, am willing to argue that he had plenty of time to visit every city in the Mediterranean region after his not exactly a death.

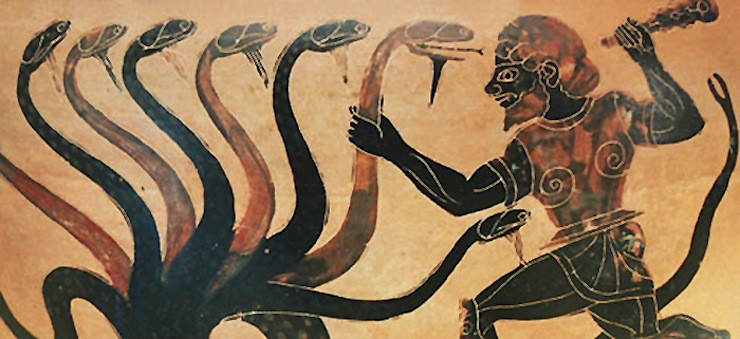

But the inconsistencies did nothing to dent his appeal; if anything, as the stories and contradictions grew, so did his popularity. He is one of the most familiar figures on Greek vase paintings, for example—paintings that help illustrate and flesh out the contradictory stories about him. And in some cases, confirm just how contradictory those stories could be. In some vase paintings, for instance, Hermes is next to Herakles as the hero captures Kereberos, the Hound of Hades, seemingly guiding him back and forth to the underworld. (Sidenote: What I love about many of those paintings? Hermes’ hat. It’s always a great hat. Sure, he might be a trickster sort of god portrayed as guiding people to the underworld—that is, killing them—but he wore great hats.) In other vase paintings, Herakles has to capture the Hound on his own. A few surviving vase paintings have Herakles fighting the Nemean Lion in poses I can only call very suggestive—something that, for all the tales of his various sexual exploits, doesn’t appear in the written forms of that particular story. Sometimes Herakles uses his bare hands; sometimes a sling, or a bow, or his club. Sometimes he is painted in black, sometimes in yellow. Sometimes he seems to be terrorizing others in the scene (particularly his cousin). Other times, he is depicted as a heroic savior.

Which brings me to the next point: in the surviving Greek art and literature, Herakles is more painted and sculpted than written about. This might simply be an accident of chance—many, perhaps most, ancient Greek manuscripts have not survived the ravages of the time. Or, perhaps, as fun as the stories were, no ancient Greek author felt compelled to write the story up as a saga to compete with The Iliad. And many of the paintings hardly need words to be understood. But it does make Herakles, unusually enough for this Read-Watch, a character more known from ancient times through paintings than stories.

The Romans, too, loved Hercules, raising temples to him and putting his images on several coins. Despite his awkwardly divine status, not exactly a Christian element, Hercules continued to be a role model in the Middle Ages, praised for valor and strength. He was the subject of multiple paintings from the Italian Renaissance and onwards, for both his heroic and sensual feats.

And in the 20th century—at least 3000 years after the first stories of him were told—the superhero entered a new artistic medium: film. The superhero was, after all, not under copyright, which allowed the Three Stooges to join Hercules for, and I quote, “More Fun Than a Roman Circus!” without having to deal with any of the tedious rights issues that surrounded more modern superheroes. A total of 19 films featuring Hercules were filmed in Italy alone starting in the late 1950s, many of them ending up on Mystery Science Theater 3000. On a more negative note, we can also blame Hercules, in a small way, for bringing us Arnold Schwarzenegger. On a more positive note, Hercules also spawned several TV shows, most notably the 1990s series starring Kevin Sorbo. And, perhaps inevitably, this ancient superhero made it into comics, stalking through both DC Comics (as part of Wonder Woman’s supporting cast) and Marvel (as, among other things, one of the Avengers.)

One blog post, alas, can’t fully cover all of the stories, texts, painted vases, statues, temples, coins, and other versions of Herakles through the years. What I can say is that none of this—not even the Schwarzenegger film (the 1969 Hercules in New York, which I have not seen, but which Schwarzenegger himself reportedly said could be used by terrorist interrogators)—could kill the ancient hero’s popularity. Quite possibly why, when looking for a film that would absolutely, positively, have popular appeal, Disney executives picked Hercules—even though it was a film that nobody at Disney actually wanted to make. Including the directors. More on this next week.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.